Mansfield Photography

Gonzales, Texas

– Where a Cannon Sparked a Revolution.

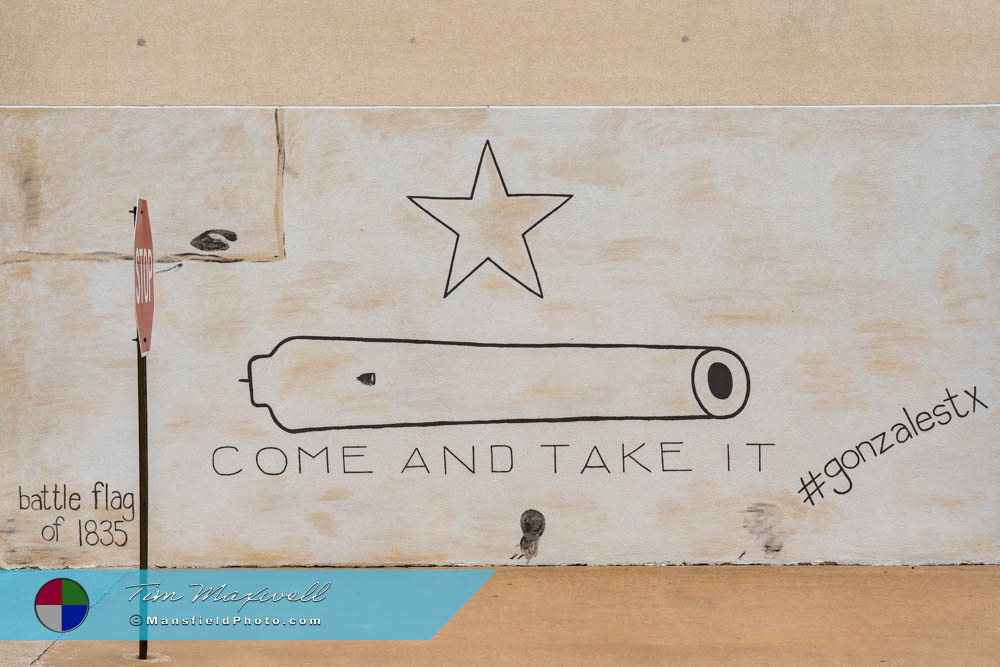

Gonzales, Texas may not be the largest or most talked-about city in the state, but it holds a unique position as the birthplace of the Texas Revolution. This small town played an outsized role in the struggle for Texas independence and has become a symbol of defiance, perseverance, and pride. It all began with a cannon, a flag, and a simple but bold phrase: “Come and Take It.”

The Founding of a Frontier Capital

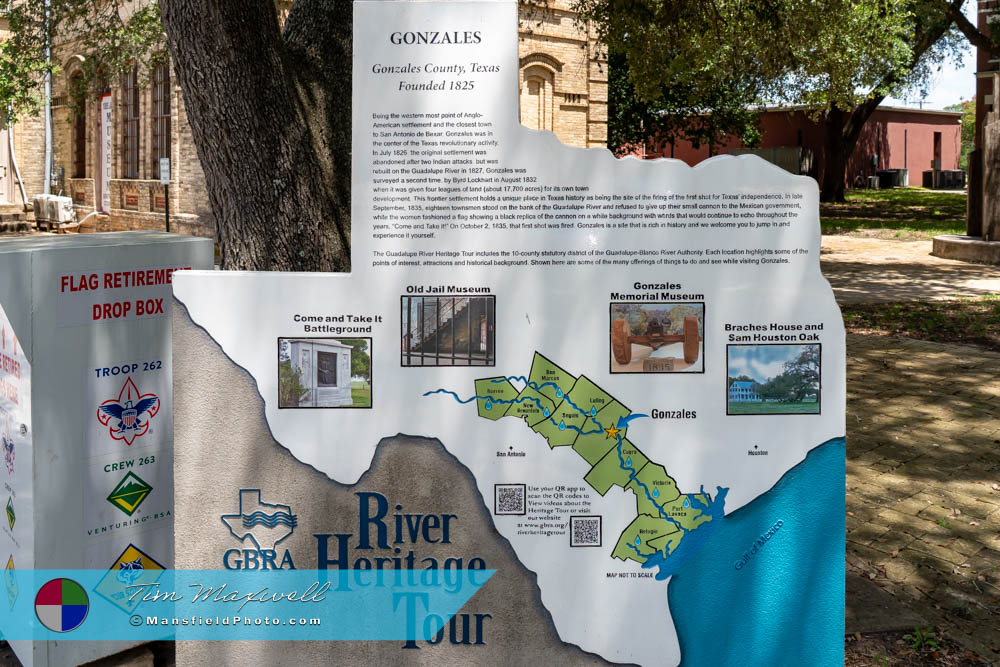

The town was established in August 1825 by Empresario Green DeWitt, who received permission from the Mexican government to settle 400 families in what was then northern Mexico. DeWitt chose a site along Kerr Creek, near the confluence of the Guadalupe and San Marcos Rivers, making it the first Anglo-American settlement west of the Colorado River. He named the community in honor of Rafael Gonzáles, then the governor of Coahuila y Tejas.

The initial settlement faced immediate hardship. In 1826, repeated Indian attacks forced its abandonment. The town was rebuilt in 1827, just a short distance from the original site, and by 1833, it was a flourishing hub and the capital of the DeWitt Colony. The layout of the town was designed in the form of a cross, with seven public squares — a rare and thoughtful urban plan in frontier Texas.

The Spark That Ignited a Revolution

In 1831, as Indian threats continued, Green DeWitt requested a small cannon from the Mexican government for defense. The government complied, sending a bronze six-pounder to the community. However, by 1835, tensions between the Anglo settlers and Mexican authorities had risen dramatically. When Mexican officials in San Antonio de Béxar demanded the cannon be returned, the townspeople were suspicious. The settlers saw the request not as routine, but as an attempt to disarm them in advance of a larger crackdown.

On September 29, 1835, a Mexican detachment led by Lieutenant Francisco de Castañeda arrived with about 150 soldiers to retrieve the cannon. But there were only 18 men in Gonzales at the time — the “Old Eighteen.” These determined settlers refused to surrender the weapon. Instead, they stalled for time while they called for reinforcements from neighboring settlements.

In preparation for a confrontation, the cannon was hidden in a peach orchard belonging to George W. Davis. Volunteers began arriving from the surrounding countryside, swelling the resistance’s numbers. Among the locals who played a key role was Andrew Ponton, the town’s alcalde (mayor), who outright refused to comply with the Mexican demand.

By the early hours of October 2, the Texians had moved upriver near what is now the town of Cost, Texas. There, they crossed the Guadalupe River and surprised the Mexican forces at dawn. Before opening fire, they raised a handmade flag — sewn by Sarah DeWitt and her daughter — that bore an image of the cannon with the defiant slogan: “Come and Take It.” The first shot of the Texas Revolution was fired.

Lexington of the Lone Star State

The skirmish was brief, but its significance was enormous. Although only one Mexican soldier was killed and the rest retreated, the Battle of Gonzales sent a clear message: the Texians were willing to fight. This minor clash galvanized resistance across Texas, and in many ways, it paralleled the Battle of Lexington that sparked the American Revolution — thus the town’s enduring nickname, “The Lexington of Texas.”

After this first battle, the town became a rallying point. Volunteers poured into Gonzales, and it quickly became the headquarters for the fledgling Texas Army of Volunteers. Just months later, after William B. Travis issued his desperate plea for reinforcements at the Alamo, it was from here that the Gonzales Ranging Company — 32 men strong — set out to answer the call. They were the only reinforcements to arrive, and every one of them perished in defense of the Alamo.

📸 Interested in More Photos of This Town?

The Runaway Scrape and the Burning of Gonzales

Following the fall of the Alamo, survivors such as Susanna Dickinson and Joe, a servant of Travis, brought word to Gonzales. Sam Houston, then assembling a force in the town, immediately realized that Gonzales would likely be the next target of Santa Anna’s advancing army.

Under the shade of what became known as the Sam Houston Oak near Peach Creek, Houston gathered his troops and issued an order that would mark yet another turning point. To prevent the enemy from gaining supplies or shelter, he commanded that the entire town be burned. The people of Gonzales — many of them now widows or fatherless children — fled eastward in what became known as the Runaway Scrape. Cold rains, mud, and disease plagued the evacuees, but this retreat gave Houston time to prepare for the decisive battle to come.

The pain of abandonment was real, but from it came eventual triumph. Just weeks later, Houston’s forces crushed Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto. The revolution had begun in Gonzales — and with it, a new republic was born.

📍 Does Texas Revolution fascinate you?

Don’t miss our article on Goliad, Texas, with a powerful and sobering connection to the struggle for independence: Goliad, Texas – Nine Flags and the Price of Freedom.

Rebuilding and Growth

In the years following the revolution, settlers slowly returned to the scorched land along Kerr Creek. Gonzales was rebuilt on its original site in the early 1840s. By 1850, the population had grown to about 300. The decades that followed saw further growth, particularly after the Civil War and the arrival of immigrant populations, including many Jewish families who became merchants and traders in the developing town.

By 1900, the population had surpassed 4,000, and the city had grown into a bustling trade center. It remained an important community for agriculture and cattle, and its strategic location between San Antonio and Houston helped maintain its relevance.

The Town Today

Modern-day Gonzales still wears its history with pride. Visitors to the town will find one of the most authentic and intact 19th-century town plans in Texas. The seven original public squares remain in place, as does the elegant 1894 Gonzales County Courthouse, a Romanesque Revival masterpiece by architect J. Riely Gordon.

The town is also home to the Gonzales Memorial Museum, where the famous “Come and Take It” cannon is displayed. Historic homes line the streets, and the community continues to preserve and honor its central role in Texas independence.

Every year, on the first full weekend of October, Gonzales comes alive during the “Come and Take It” Celebration. The event includes a reenactment of the 1835 skirmish, parades, food vendors, crafts, live music, and educational exhibits. It’s more than a festival — it’s a living memory of a time when ordinary people took an extraordinary stand.

A Town That Stood Its Ground

The story of Gonzales is not just one of military encounters or political revolution. It’s a story of people — the Old Eighteen, the Come and Take It flag-makers, the widows of the Alamo defenders, and the families who rebuilt after the flames. Their courage and resilience left an imprint on Texas that will never fade.

In every cannon echo, in every banner bearing that bold phrase, Gonzales continues to remind Texans what it means to stand up — even when the odds are long. Come and take a look for yourself.